Carpenter at 44: Still Master of the Ascent

I was pleased to see this fantastic profile of Matt Carpenter in the New York Times on Monday. Carpenter, one of our local Colorado runners, has long been associated with the Pikes Peak-area Incline Club and among his many running accomplishments, his records for the Pikes Peak Ascent & Pikes Peak Marathon still stand. Enjoy -- and see you on the trail!!

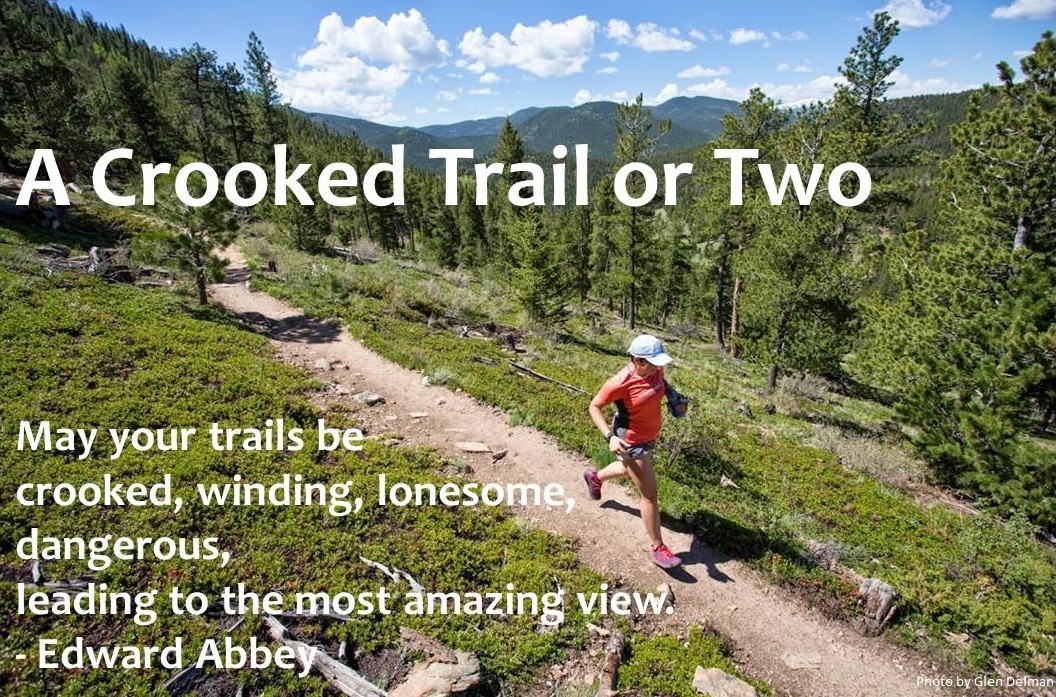

Photograph by Kevin Moloney for the New York Times.

At 44, a Running Career Again in Ascent By Michael Brick

Published: February 23, 2009

MANITOU SPRINGS, Colo. — The course follows old Ute tribe trails 20 miles up, down and around Pikes Peak, a narrow, gravelly passage rising 7,815 feet to crest 14,110 feet above sea level. Tourists with respiratory ailments are cautioned against making such an ascent, even by car. Motorists on nearby roads are advised to employ manual transmission. Promotional materials for the summit warn of altitude sickness, lightning, hypothermia, rattlesnakes and wild animals carrying bubonic plague.

Matt Carpenter expected to run it in about three hours.

At 44, Carpenter is known as the grand paladin of high-altitude distance running. In 1993, he set record times — still standing — for the 13.3-mile Pikes Peak Ascent and the Pikes Peak Marathon, races he won again in 2001 and 2007, both times on consecutive days. He has also set speed marks in a high-altitude flat-surface marathon, a 50-mile race and a 100-mile race.

In 2002, after his marriage, the loss of his sponsorship and the birth of his daughter, Carpenter was considered a champion in eclipse. Nearing his 39th birthday, he won only the familiar Pikes Peak Ascent, with a time 22 minutes behind his own record, and placed 33rd at another mountain race.

But as the milestones of fleeting youth have given way to the slipstream of middle age, Carpenter has returned to form. Last year, he won six long-distance races, setting two course records. And he is training for the Teva Mountain Games in June in Vail, Colo.

“Whenever we race, I know it’s going to be a good competition — unless it’s at high altitude, and then I don’t stand a chance,” said Uli Steidl, 36, who placed second behind Carpenter at a 50-mile race in San Francisco in December.

In part, Carpenter has owed his prowess to his physiology. His resting heart rate has been measured at 33 beats a minute, lower than those of Michael Phelps and many astronauts. In a test at the United States Olympic training center in Colorado Springs, Carpenter’s VO2 max, a gauge of the body’s ability to process oxygen, registered at 90.2, perhaps a record high for a runner. (Only Bjorn Daehlie, a Norwegian cross-country skier, has scored higher. Lance Armstrong recorded an 81.)

Still, cardiorespiratory capacity can take an athlete only so far. Carpenter runs at least three hours every other day. On alternate days — rest days, he calls them — he runs an hour and a half. Though weather seldom impedes him, he owns a $10,000 220-volt treadmill with three motors capable of providing an impossible pace of 3 minutes 20 seconds a mile on a 27 percent grade. And he lives here, at the base of Pikes Peak.

No rigorous antidoping program exists in high-altitude trail running, primarily because such an effort would be prohibitively expensive. Carpenter has never been publicly accused of doping; he said he has never taken performance-enhancing drugs and was happy to be tested any time.

“He trains as hard as he needs to win, and then he’ll do a little more,” said Nancy Hobbs, the executive director of the American Trail Running Association.

A stick figure at 5 feet 7 inches and 122 pounds, with pinched features and bright blue eyes, Carpenter wears a mop of unkempt hair that gives him the appearance of a sideman for a rock band reunion tour.

Born in Asheville, N.C., he moved from state to state with his mother, who was divorced, sickly and struggling to hold down work, he said. By his account, he spent his childhood in rabid pursuit of arbitrary goals. Whole days were given to throwing a tennis ball against a wall. He once held his breath underwater until he blacked out. In high school, a class schedule conflict deposited him on the cross-country team.

“I actually thought we were going to run across the country,” Carpenter said. “I thought we’d get out of school a lot.”

As a teenager, Carpenter learned that the man he had believed to be his father was actually his adoptive stepfather. In his freshman year of college, his mother committed suicide. For years, he dreamed of his biological father, who eventually tracked him down through his running career.

“I’d always made him whatever I wanted to be,” Carpenter said of his father. “If I felt poor, I made him a rich guy. If I needed an athlete, I made him a fast runner.”

Carpenter did not find his stride as an athlete until his mid-20s. In 1989, he left a computing job to focus on running. He won 7 of his first 14 races. Two of them had the word “climb” in their name; a third, the Pikes Peak Marathon, did not need to.

In 1993, an Italian group called the Skyrunners recruited Carpenter to run a marathon on a high-altitude flat course in the Himalayas. He spent the next seven years traveling the world for Fila. The company cast a mold of his feet for custom shoes.

“They’d point to a mountain, and we’d run up it,” Carpenter said. “I felt with every race that somebody was trying to beat me and take away my sponsorship.”

Though he found relatively little success on traditional courses, placing 42nd at the Boston Marathon in 1995, Carpenter won 15 of the 17 high-altitude marathons he entered in the next seven years. He founded a group called the Incline Club, leading weekly training runs around Pikes Peak. He married a member, Yvonne Franceschini, in a ceremony on one of the group’s outings. The newlyweds tied cans to their backs and ran home.

Every Sunday, Carpenter has returned to lead the club’s training runs, proselytizing local joggers with his training philosophy: “Go out hard; when it hurts, speed up.”

In 2000, Fila dropped the Skyrunners program, said Lauren Mallon, a spokeswoman for the company. On July 9, 2002, to celebrate the birth of his daughter, Kyla, Carpenter ended a streak of running on consecutive days for 5 years 57 days. He stopped doing his sit-ups, took shortcuts, slept poorly and started losing races.

“Somebody told me you don’t know who you are until you do a 100-miler,” Carpenter said. “I said, ‘Damned if I’m going to die and not know who I am.’ ”

So Carpenter started lifting weights. He strengthened his core muscles. He enlisted his wife and daughter as crew members. Soon, family life turned into something resembling the “Gonna Fly Now” montage, only with more running.

In August 2004, Carpenter entered the Leadville Trail 100, known as the Race Across the Sky. Partway through, his quadriceps gave out. Sometime after midnight, walking the last 30 miles with his knees locked up in the manner of Dr. Frankenstein’s monster, Carpenter finished in 14th place.

A year later, Carpenter returned to beat his own time by seven hours, win the race and break the course record by 93 minutes. Since 2005, he has won 13 more distance races, including a 50-miler. No one has beaten him in the marathon on Pikes Peak.

“A lot of people say you want to quit at the top of your game, but I don’t want to quit at the top,” Carpenter said. “I want to know where the edge is, and I want to know when it’s going to stop, and if I slow down and drag out running, so be it.

“At this point, I like that fine line of balancing right between injury and not injury, seeing what I can get out of my body. Sometimes I lie in bed at night and wonder if I’ve done all I can, and if I haven’t, I go out at night and do more.”

Just after dawn one Sunday last month, as a light snowfall prettied the old town square, Carpenter led a group of runners past buildings here with names that seemed to taunt: the Iron Springs Chateau Melodrama, a dinner theater; and Our Lady of Perpetual Help, a church. The group made a sharp right turn at the outskirts of town, climbing into the mountains.

Here, snow-muddled conifers canopied the trail like some desert Sleepy Hollow. The runners trudged upward, ignoring the bitter cold, the twilit vistas, the call of some distant wild thing attacking its breakfast. Three hours later, breathing steadily, Carpenter quizzed his charges, climbed into his sport-utility vehicle, and set off to fix a peanut butter sandwich.

“It’s neat,” he said, “to see all these other people develop a passion.”