Week 31: The Highland Boundary Fault to Dalwhinnie

Happy Valentine’s week, friends. Here in Colorado, the week brought record cold temperatures, with an arctic blast bringing weather that was about 30 degrees below the normal averages for the middle of February. The recent polar plunge included five consecutive subzero overnight lows, something that has only happened twice this century.

The coldest morning was Feb. 15, when the mercury plummeted to -16°F. It was the lowest temperature recorded in Denver since Dec. 30, 2014, when the day started at a bone-chilling -19°F.

So, wherever you are, I hope you’re staying warm!

Certified guide in Scotland, Kirsten Griew

And now… back to our virtual trek the length of Great Britain!

For the past few weeks, we have been lucky enough to have certified Blue Badge guide for Scotland Kirsten Griew sharing stories and history as we continue making our way north. Kirsten too is participating in our journey from Land’s End to John O’Groats, moving virtually over terrain she’s seen in real life.

What follows today comes from mainly from Kirsten, with just a few notes thrown in from me. Thanks, Kirsten… and enjoy, friends!

We ended last week at the Highland Boundary Fault, a geological line that separates the high mountains of the Highlands from the flatter, more agricultural landscape of the Lowlands, which determined the major social and cultural differences in the two areas too. The line is diagonal, running from northeast (just south of Aberdeen on the East Coast) past the city of Stirling in the middle of the country, through the middle of Loch Lomond and out to the west through the middle of some of the islands. This is why as we are travelling north on a road towards the east of the country, we have had to go relatively far north to hit it.

John Murray, the “planting duke” of Atholl

A very large proportion of Scotland is owned in massive private estates, and we’ve just made our way onto one. This one is the Atholl Estate, owned by the Dukes of Atholl (more about them as we pass their ancestral home — Blair Castle — shortly). This part of the country has trees planted by the 18th century 4th Duke of Atholl, John Murray, often referred to as 'the planting duke.’ There were lots of high craggy hills on the Estate, so the way he planted was to have the seeds loaded into a cannon, and fired onto the hillsides! Apparently, in addition to foresting this part of Scotland, the Duke was hoping to sell the timber (most of it Larch) to the Royal Navy to build warships. But by the time the trees matured, most ships were being made of steel.

One interesting note, particularly for readers in the USA: Although most of the land in Scotland is owned privately, we also have laws protecting our freedom to roam. No landowner can keep people from hiking where they like, other than for reasons of safety.

The first town we reach on crossing the faultline here, is really two villages that have grown together: Dunkeld and Birnam.

Birnam is first, and has two literary connections.

Peter Rabbit and a bird friend, drawn by Beatrix Potter. (Image from Britannica Online)

Firstly, Beatrix Potter who wrote all the Peter Rabbit books and drew all the pictures too. She was from London, but as a child with her family, and later herself as an adult, would come on holiday every year to Birnam. The Tale of Peter Rabbit, her first book published in 1901, was written as a letter to her nephew back home. The characters in the stories are based on local people in Birnam.

One of Beatrix Potter’s studies of mushrooms

Potter studied the flora and fauna around the village, and if you look at the pictures of the animals she drew, although anthropomorphised, they are incredibly accurate depictions of the creatures. She also made detailed studies of plants and mushrooms. Passionate about nature and eager to produce accurate drawings, she sought out an introduction to Scottish naturalist Charles McIntosh, who shared her fascination with fungi and encouraged her to continue producing accurate drawings and watercolors.

As she observed mushrooms so closely, she developed her own theory of how fungi spores reproduced and wrote a paper, ‘On the Germination of the Spores of Agaricineae,’ which was presented to a meeting of the Linnean Society in 1897 by one of the mycologists from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, since women were not allowed to attend Society meetings. Her paper has since been lost, and although her theory would later be proved correct, she was ignored by the scientific community at the time because she was -shock, horror - a woman. And more than that, a woman who was, officially at least, uneducated.

King MacBeth of Scotland, painted by Dutch artist Jacob de Wet II in 1686 — long after MacBeth’s death. This portrait hangs in the Palace of Holyroodhouse that we learned about when we made our way through Edinburgh.

The other literary connection is with William Shakespeare himself and what is perhaps his most famous work: the “Scottish Play,” Macbeth. In the story, Macbeth meets three witches who predict: “Macbeth shall never vanquish’d be until Great Birnam Wood to high Dunsinane Hill Shall come against him.” Macbeth takes this as the equivalent of “When pigs fly.” However, in the end his enemies hide in Birnam Woods, tearing down branches to use as camouflage, then they move against him and indeed he is defeated.

MacBeth was a real king of Scotland who ruled from about 1040 to 1057 (right before Malcom III and Queen Margaret who we heard about last week). And the truth is we do not have a huge amount of evidence about him, which is one of the reasons that Shakespeare was able to use his story in this way. However, the evidence we do have, indicates that he was a well-loved and respected monarch, very different from the version created by the English bard.

What remains of Dunkeld Cathedral, along the River Tay, with Telford’s bridge in the background. (Photo: Historic Environment Scotland)

Dunkeld sits on the River Tay - Scotland's longest river, at 119 miles. And, if Scone was the secular capital of ancient Scotland, for a long time Dunkeld was the religious centre. Originally it was a form of Celtic Christianity that was practiced, but it moved with the times. The remains of the subsequent Catholic Cathedral are still there, picturesquely by the riverside, with the old Choir of the building now in use as the town's Church of Scotland (Presbyterian) kirk.

Today one of the major town landmarks is the bridge over the Tay, built by the great Scottish engineer Thomas Telford. Telford improved and increased the road network throughout the Highlands, particularly by building bridges in places that no one ever thought possible. Here, for example, he had the path of the river altered in order to construct the bridge. The beautiful stone arched bridge opened on March 29, 1809.

One of my favourite walks is in this area is just north of Dunkeld, along the River Braan to Ossian's Hut. Ossian is a mythical ancient Gaelic poet who, legend has it wrote in a hut by the side of the river at a spectacular waterfall just here. The myth was propagated by James Macpherson in the 18th century, who claimed to have 'discovered' poems written by this ancient bard, a Scottish version of someone like Homer.

He fooled everyone for a time, but soon it was realised that actually Macpherson had written the poems himself! However, at the height of Ossian mania, a hut was built on the same spot with a viewing area to the waterfall, and mirrors on all the other walls. In a time before television and movies, the way the gushing water reflected through the building was an extraordinary experience. In fact, it was considered so powerful, that women were banned from going in, as it was felt they would faint from the excitement!

Pitlochry (photo: Scotsman Food & Drink)

The next town up is Pitlochry. Only 3000 or so people live here, but (in a non-pandemic year) Pitlochry would probably have many times that number of visitors every day! It is the main stop on the road between Inverness (capital of the Highlands) and either Edinburgh or Glasgow. In summer, in the coach park you would generally see about 20, 50-seater coaches parked at any one time, plus all the mini-coaches and cars. It is a lovely wee town with good cafes, restaurants and some interesting places to walk to.

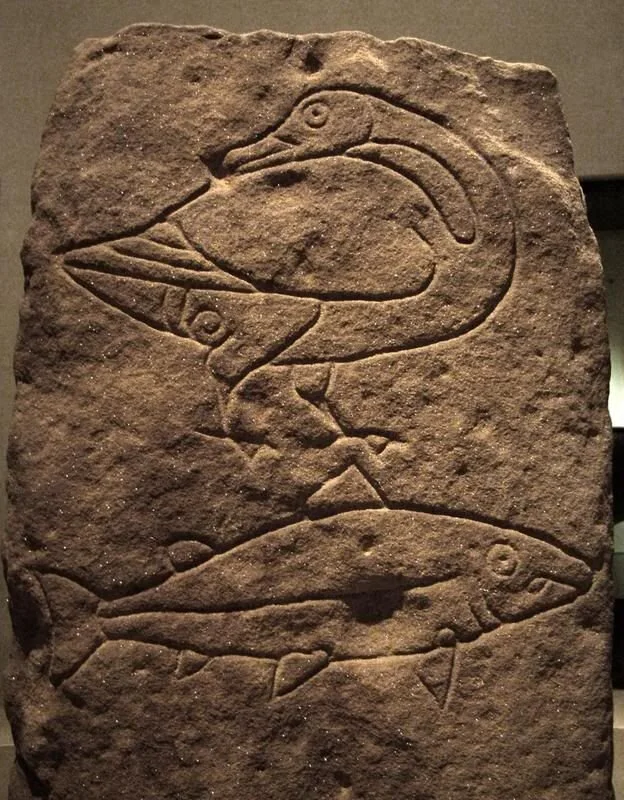

Salmon have been a critical part of Scotland’s ecosystems for millennia. This Pict-era carving depicts a salmon and a goose. (Photo: National Museum of Scotland)

Pitlochry sits on the River Tummel, which is a very important salmon run. However, in the 1950s a huge hydroelectric dam was built on the river. This caused the salmon's route to be blocked, of course, so they put in a salmon ladder which has now become a tourist attraction.

As a public relations move, salmon ladders help the general public become more accepting of hydroelectric power, perhaps thinking to themselves, “Great! With this salmon ladder in place, this dam poses no problems!” But research is showing that technological work-arounds are no substitute for actual habitat conservation, with one recent study by Yale University of three rivers in the US showing that less than 3% of the expected fish populations actually made it to their spawning grounds, despite fish ladders being in place. Salmon populations across Scotland (and around the world) continue to plummet as a result.

Mark Bilsby, of the Atlantic Salmon Trust, says that salmon are the “canary in the coalmine” warning of greater environmental disaster from habitat loss, climate change, overfishing, and other perils. “These fish,” he says, “are pretty uniquely placed. They tell you about the quality of the rivers they are living in for the first few years of their life, and also what’s happening at sea – and they’re telling us that something’s really wrong with both our rivers and our sea. That’s why salmon are important.”

A coalition of scientific and activist groups, called the Missing Salmon Alliance, is working to educate the public and urge governmental action. Here’s hoping people will pay attention so we can take action in time!

Pitlochry’s picturesque Edradour Distillery (photo: The Whiskyphiles)

For such a small town, Pitlochry is blessed with a brewery and two distilleries, including Edradour, which until recently was Scotland's smallest distillery; and Blair Athol distillery, which is one of the main single malt whiskies that makes up Bell's more famous blended whisky, the most popular Scotch whisky in the U.K. (Note: in Scotland whisky is spelled without an 'e').

Beyond Pitlochry is the Pass of Killiecrankie. This ravine is famous as the sight of the Battle of Killiecrankie. This was one of the battles in the first of the Jacobite Uprisings. The uprisings started when King James VII of Scotland - also King of England, where he was James II - converted to be Catholic on marrying his second wife. By this time both Scotland and England had long been Protestant, so in 1688 the parliaments of both countries threw him out - he was exiled to France.

James already had 2 Protestant daughters by his first wife, and the eldest of these, Mary, married a cousin, William from the Netherlands, and they became joint rulers. Those who objected to this change of regime became known as Jacobites, which is from the Latin for James (Jacobus). There were many Jacobites amongst the Highland Clans, so this is where many of the battles took place.

A reimagining of the Battle of Killiekrankie Pass by 20th century artist Alan Herriot

Soldier’s Leap (photo: ScotClans.com)

Killicrankie in 1689 was the last of the battles in the first uprising, led by John Graham of Claverhouse, 1st Viscount Dundee, on the Jacobite side. He was known as Bonnie Dundee to his supporters, and Bluidy Clavers to his enemies... and he died there, legend claims, while sitting against a monolith which has since become known as Claverhouse's Stone. At the battle, Jacobite soldiers escaped those sent by William and Mary by jumping across a wide, treacherous stretch of the river at a place now known as Soldiers' Leap.

Soon after this we pass the town of Blair Atholl, which is the location of Blair Castle, ancestral home of the Dukes of Atholl.

Blair Castle (photo by Simon Jauncey)

The oldest part of the building dates from 1269 and is known as Comyn’s Tower; like many of the ancestral homes we’ve visited, Blair Castle was changed many times over the centuries, with the bulk of today's building dating to the 18th century.

Sarah Troughton, who currently manages Blair Castle.

The current (12th) Duke does not live here, but rather in South Africa — as did his father. The last duke to live here - the 10th - died without any children, and the succession rules dictated that the line could not go through a female heir. So although the Duke's half-sister, Sarah Troughton, had sons, they could not take the title. In fact they had to go back through the family tree as far as the 3rd duke, and the next living relative traced entirely through a male line was John Murray living in South Africa. He had a nice life there and didn't want to move, even to a huge grand castle in the Highlands! Same with his son Bruce, the current duke after John died in 2012. Whilst the title has to go through the male line, the estate itself is held in a trust, managed by Sarah Troughton and her son, Robert.

Other than the title, the Duke keeps one other unique characteristic: He is the head of the only private army in Europe, the Atholl Highlanders. The Highlanders are not a fighting force, although legally they could be since being granted the status by Queen Victoria. The army is made up of people from across the estate who choose to sign up. They have a kilted, besporranned uniform, and march on special occasions. Every May, the Duke still travels in from South Africa to review his troops.

The Atholl Highlanders during Gathering Weekend (photo from Blair Castle website)

Past Blair Castle we pass through the high Pass of Drumochter. The train tracks that run through the pass alongside the road are the highest stretch of railway line in the UK, and the Pass is subject to all the weather extremes that one would expect from high ground. (High for the UK, that is! The high point of the pass is 1,508 feet — around the same elevation as Fayetteville, Arkansas or Tempe, Arizona — but you can see the terrain looks very different from those places!)

The Druim Uachdar Pass as seen upstream from the west side of the railway. (Photo by Richard Webb)

The Wade Stone (photo by David Glass)

Close to the road here is the Wade Stone, placed to mark the building of the original roads through the Highlands, under the supervision of General Wade. They were designed as military roads, after the second Jacobite Uprising in 1715. The idea was to allow the military to easily travel through the Highlands to supress any future uprisings. The A9 roadway we are on closely follows the route of one of those original roads.

Finally today, we reach Dalwhinnie. This is a small town with another very well known whisky distillery! Dalwhinnie is well loved as a Single Malt in many parts of the world. It has very traditional distillery architecture, with whitewashed walls and the pagoda style chimneys which would have kept out the rain whilst allowing smoke to escape. This was in the days when they would malt their own barley onsite. Like most distilleries in Scotland today, Dalwhinnie brings the barley in already malted. (Malting is the process where the barley is spread across the malting barn floor, dampened so that the seed starts to germinate and produce sugars, then put into a kiln — an oven, sometimes fueled by peat to create a smoky flavor — to dry it out.)

Dalwhinnie Distillery on one of its warmer days. ;-)

It is the highest distillery in Scotland and regularly gets snowed in (it is probably almost roof high there right now, considering the amount of snow we have currently in Edinburgh!). In 1994, it was confirmed that Dalwhinnie has the coldest average temperature of any inhabited Scottish region (-6 degrees Celsius, or 21 degrees Fahrenheit).They actually have accommodation for the staff at the distillery in case they get snowed in at work and can't get home... Production stops for nothing!

One additional note from Ashley:

This stretch of Scotland brings to mind former Scots Makar (Scottish Poet Laureate) Liz Lochhead, as her poem Favourite Place references sites just off to the west of this stretch of road: Ballachulish, Loch Linnhe, Mallaig… She was first introduced to me by my friend (and Smithsonian Journeys Expert) Cassandra Potts Hannahs, who around the time we began our journey from Land’s End to John O’Groats, mentioned that the first time she remembered hearing the expression “from John O’Groats to Land’s End” was in a recording Lochhead made of another poem of hers: “Kidspoem/Bairnsang.”

As Cassandra explained at the time, the poem deals with language and identity in Great Britain, specifically with growing up speaking Scots and having to learn RP English in school. Although the introduction in this video is a bit long, hearing her read the poem is definitely worth the wait. And as Cassandra said, “When I teach it, everyone always goes “Ahh” at the ending.” I did too!

Definitely give it a listen, & enjoy, friends!

Fancy a pint?

Unlike the Naylor brothers, who pledged to “abstain from all intoxicating drink” during their 1871 walk on this route, I’m not at all opposed to popping into interesting-looking pubs along the way. Here are a few along this stretch of the journey… this time, curated by Kirsten Griew, who has actually been there in person!

The Taybank, along the River Tay in Dunkeld

The Taybank is a lovely sprawling pub with a terrace and garden, and has ong been known for its great music and fantastic setting on the banks of the River Tay. In addition to the beergarden where people can enjoy a drink and a bite to eat, the gardens also are a site for growing vegetables, herbs and flowers that are used on site.

In Pitlochry, the Old Mill Inn offers drinks, comfy accommodations, and live music. Situated along a stream, the mill was operational throughout the 1800s and was later converted into a pub. Its current owners conducted a major renovation/restoration of the building in 2012.

The menu offers typical pub favorites AND chef-designed specialties… including vegan options!

The Old Mill Inn, in Pitlochry

The Moulin Brewery in Pitlochry

And also in Pitlochry, visiting the Moulin Brewery will allow us to sample the local brews, in a historic location. The brewery is housed within the Moulin Hotel, which originally served as a coachhouse & stables for the Pitlochry to Kirkmichael coach service.

Sustenance for the Hungry Vegan

In a two-acre woodland overlooking Pitlochry, Saorsa 1875 is an all-vegan hotel dedicated to showcasing what it calls “ethical luxury.”

The 19th-century baronial house has 11 unique bedrooms, while downstairs the lounge and restaurant offers a completely plant-based menu that showcases local, seasonal and foraged produce - all washed down with craft beers, a unique wine list and cocktails inspired by the region. What’s not to love?!

All-vegan hotel Saorsa 1875, in Pitlochry

Hettie’s Tea Room in Pitlochry

I love Hettie's Tearoom, which has wonderful tea, soups and scones. The tea comes with a mini-eggtimer to let you know when it is perfectly brewed.

Though not mentioned on Hettie’s website, Happy Cow indicates it has a separate all-vegan menu featuring soups, soups, sandwiches, main meals and desserts.

Café Calluna in Pitlochry

Café Calluna offers wonderful baked goods and light meals, including many vegan options. The menu changes regularly according to what’s in season, but online reviewers especially praise the carrot cake and the soups… and the fact that the café is dog-friendly.

The Watermill in Blair Atholl

Finally, in Blair Atholl, I really like the Watermill Café: a working water mill dating back to 1590s where stoneground oatmeal and flours are milled and sold.

In the tea room, they offer freshly baked cakes, scones, a variety of breads, bagels and rolls, as well as homemade soup and light lunches. Everything is made fresh and from local produce where possible.

Cheers, everyone, and see you on the trail!