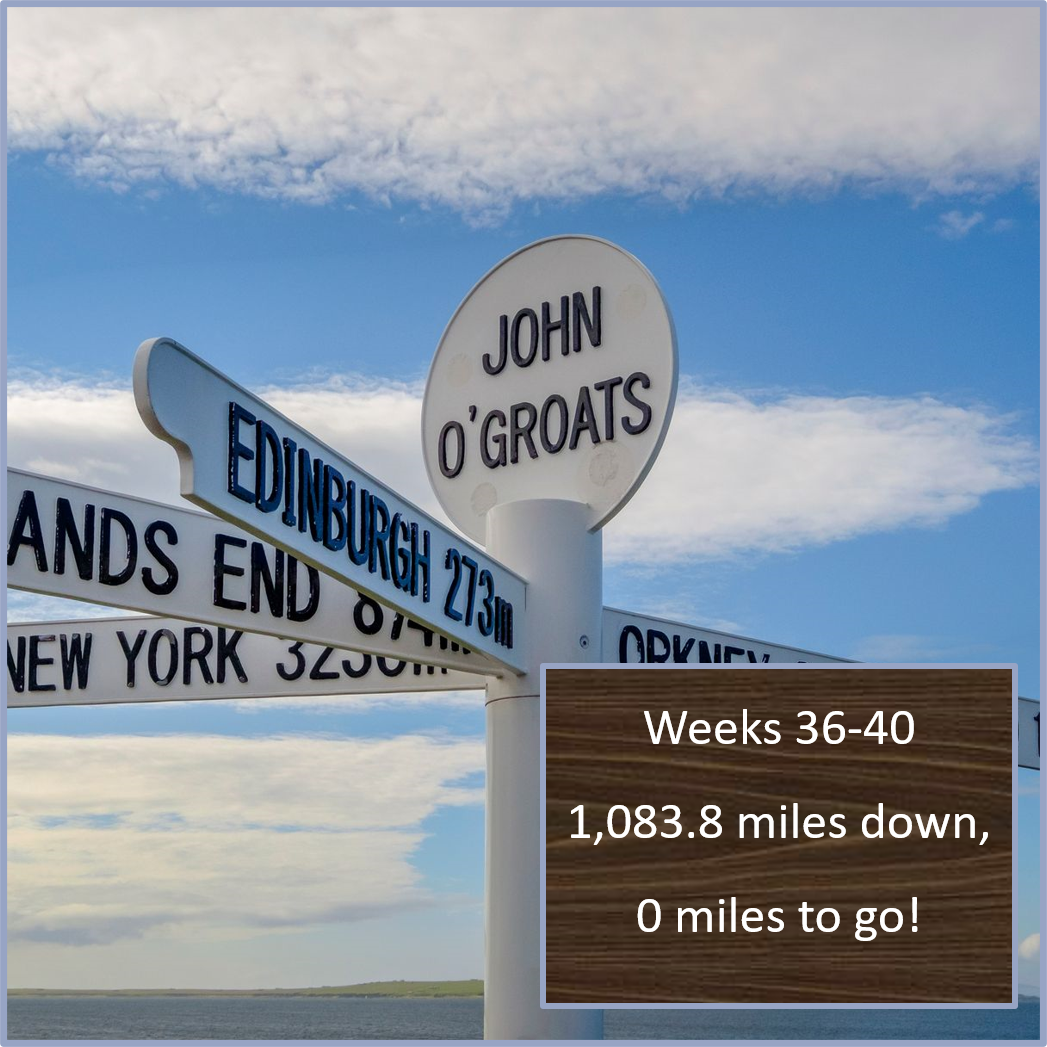

Weeks 36-40: The Dornoch Firth to John O'Groats

Last July, when I embarked on this 1,084-mile virtual journey, I was looking to keep my running on track, entertain myself during the pandemic, and learn something new along the way. Well, mission accomplished in every way! I have loved getting to explore this unique island with all of you. Thank you! This has been much more fun than I expected, and I have learned SO much along the way.

I extend my thanks to Cassandra Potts Hannahs for sharing stories and sites along the way, and extra-special thanks to Kirsten Griew, whose guest blogs have guided us through Scotland. I appreciate you both taking the time to share stories and places that helped the rest of us learn more about the places we were passing through. Thanks too to Dad, David and Tom, as well as Cassandra and Kirsten, for coming along for the virtual journey. It’s been great having your company all the way!

A journey of 1,083.8 miles comes to a close, with the Rocky Mountains in the background.

The real-life final leg I ran to complete this journey couldn’t have been more different from the actual final seven-mile stretch to John O’Groats. I couldn’t find seven miles of flat-enough trail near me to come close to approximating it. So yesterday, I ran the final stretch up Towers Road, ending at 7,110 feet (compared to John O’Groats, basically at sea level) with this flat stretch of land in mind as I climbed almost 2,000 feet over the course of 50 minutes. But that’s the magic of a virtual challenge: it allows you to experience, from a distance, a place that is totally different from wherever you actually are.

It’s pasqueflower season in our mountains.

The view from the top of Towers Road.

A Google Street View of the last stretch to John O’Groats.

A Google Street View image, looking out to sea from John O’Groats.

Certified guide in Scotland, Kirsten Griew

So, without further ado, let’s bring this journey to a close and learn more about the stretch from Dornoch Firth to John O’Groats!

For the past few weeks, we have been lucky enough to have certified Blue Badge guide for Scotland Kirsten Griew sharing stories and history. Kirsten too is participating in our journey from Land’s End to John O’Groats, moving virtually over terrain she’s seen in real life.

What follows today comes from mainly from Kirsten, with just a few notes thrown in from me. Thanks, Kirsten… and enjoy, friends!

Our last post focused on the three firths north of Inverness: Moray, Cromarty, and Dornoch. The rest of our journey hugs the east coast of Scotland, never straying far from the North Sea all the way to our destination of John O’Groats.

On crossing over the Dornoch Firth, we have entered into the area of Scotland called Sutherland. If you were to draw a line across the country directly east to west here, everything to the north is Sutherland (other than a small corner in the far north east called Caithness).

For many centuries this was all one single estate, owned by the Duke of Sutherland - making it, over that time the largest private estate in Europe. The Duke was one seriously wealthy man. From here (and from everywhere around) there is a clear landmark - a massive 100 foot statue of the Duke on top of a hill already 1300 feet high. It was designed to be visible as far and wide as possible.

The Duke of Sutherland Monument (photo: KentPhotoPics)

It was erected by the Duke's widow on his death, and has a horribly ironic plaque claiming it was paid for by 'a grateful and mourning tenantry.’ The Duke had, during the early 19th century presided over some of the cruelest and harshest evictions during the Highland Clearances. His factor (a factor is a land manager in Scotland), Patrick Sellar, had forced people from their homes, burning houses down, pulling others down to piles of rubble, killing some of the residents in the process. Sellar was tried in Inverness for multiple homicide, but let off by a jury of his peers. Most of those who left were put on boats to the 'New World' as it was then - America, Canada, Australia, New Zealand... Mostly they did find an easier and better life in America, but that was only if they survived the cruel evictions and the horrific, overcrowded sea voyage there.

Because his legacy is distinguished by such brutality, there have been multiple attempts over the years (some legal, some not-so-legal) to bring down the Duke of Sutherland statue. As with Confederate statues in the USA, the conversation in Scotland is continuing, regarding the appropriate role for the statue in our times.

Shortly after passing right underneath Ben Bhraggie and the statue, we reach Dunrobin Castle, the traditional home of the Dukes of Sutherland. It is one of the most extraordinary places to visit in Scotland. It looks like a great French chateau, perched on top of sea cliffs, looking out across magnificent formal gardens (where some excellent falconry displays take place).

Dunrobin Castle (photo: The Northern TImes)

It sits on the site of a very early fortress. There is some of the medieval castle hidden in the middle of the building, but the exterior is 19th century. Very lavishly designed by Sir Charles Barry, who had been the architect for the Houses of Parliament in Westminster (Downton Abbey fans: he also designed Highclere Castle, where the TV series was filmed). After a fire in 1915, the interiors were all completely redone, by another very well regarded Scottish architect, Sir Robert Lorimer.

The Seamstresses’ Room at Dunrobin Castle (Photo: Dunrobin Castle)

Of course, there is a ghost story. It is rumored that in the room now called the Seamstresses’ Room, a young woman from the McKay clan was locked away by the Chief of the Sutherlands. The Sutherlands and McKays had a feud dating to before the 16th century. This young daughter of the McKay chief had caught Sutherland's eye, so he decided to kidnap her, imprison her and then force her to marry him. Whilst locked in this room, so horrified by the idea, she tried to escape with the trick of tying bedsheets together to form a rope. She was lowering herself out of the top story window, when Sutherland came in, saw what she was doing, and in a rage cut the sheets, so that she fell to her death. As the story goes, her ghost is now sadly stuck in this room.

Just north of Dunrobin Castle we pass by Carn Liath, a very well preserved broch.

Carn Liath (photo: the Mobile Megalithic Portal)

A drawing showing what the inside of a broch may have looked like (drawing by Alan Braby on the Broch Blog)

Brochs were built at strategic locations all the way around the coasts of Scotland's Highlands and islands around 200BC-200AD. Today, most are no more than a stone or two, but the best preserved example is at Mousa in the Shetland Islands, followed by Dun Carloway on the Isle of Lewis, and then this one. These were circular stone towers, built with double walls with staircases between them. They were about 30 feet high and would have had a thatched roof.

We still don't know exactly their original function, however, there are theories about their use as lookouts. This is backed up by their positioning on the coast (threats would have come from the sea), spaced out at distances that would have allowed for a signal by fire.

They were often built with two towers facing one another across a stretch of water between mainland and island. Around the brochs, the remains of other smaller buildings are often found, leading to theories that they might have been the central buildings of small communities, whether as the chief's home, or as a central gathering place - perhaps both. And of course, all of these could be true at the same time. The name of this one translates as carn = cairn which we know is a pile of stones, and liath is grey... early peoples finding it presumably did just see a grey pile of stones!

A photo showing what many broch sites look like, and the interpretation required to figure out how the site may originally have functioned. This is at on Papa Westray island. (Photo: the Broch Blog)

Further north, we go through the town of Helmsdale. It was founded in 1818 by the Countess of Sutherland as a herring fishing settlement, with the idea that some of the farmers being thrown off the farmland during the Clearances would have alternative employment. The bridge and harbour built around that same time were by Thomas Telford (the great Scottish engineer who also built the Caledonian Canal along the Great Glen).

Thomas Telford’s bridge in Helmsdale (photo by Wikimedia user Ian Paterson)

Sadly, Helmsdale Castle that was on the promontory between the sea and the River Helmsdale was removed entirely in the 1970s (it was a ruin) to make way for a road project. It dated back to 1488. In 1567 the 11th Earl of Sutherland was poisoned in the Castle by his aunt, Isobel Sinclair. She wanted her own son to take the title (and properties). Her plan backfired, however, as her son also drank the poison and died. Isobel was found guilty and sentenced to be hanged as punishment, but took her own life before that could happen. Apparently, this true story inspired Shakespeare's Hamlet.

A 1940s-era photo of the ruins of Helmsdale Castle (photo from the BBC)

Inland from Helmsdale, further upstream on the river is the Strath of Kildonan. During the Clearances nearly 2000 people were cleared from their homes in 1812, many of whom travelled to Manitoba in Canada. This included George Bannerman and Christina Sutherland Bannerman, whose great-grandson was John Diefenbaker who became Prime Minister of Canada in 1957.

The Strath (wide valley) was also the site of great excitement in 1869, when a returning Highlander, Robert Gilchrist, who had emigrated to Australia, found gold in one of the tributaries of the River Helmsdale. Around 500 prospectors arrived, and two temporary settlements were established. One was a hutted shanty town on the edge of the Kildonan Burn at Baile an Or: Gaelic for “Town of Gold.” The other was Carn na Buth, or “Hill of the Tents” on the edge of the Suisgill Burn.

The hut town of Baile an Or in 1869 (photo: Undiscovered Scotland)

The gold craze didn’t last long, though, due to the effects their activities were having on deer stalking and fishing. When the Duke of Sutherland found he was losing more potential income from hunters and fishermen than he was gaining from the prospectors he announced that all exploration for gold would cease on January 1, 1870… so the Strath Kildonan gold rush quickly came to a close.

A Scottish Wildcat in the wild (photo: Tony Hamblin)

We now face quite a climb on the road as we cross over the hill called the Ord of Caithness. It separates the area of Sutherland from Caithness, the most northeasterly corner of mainland Scotland. Both Sutherland and Caithness are names with Norse origins. Sutherland is interesting as, exactly as it sounds, it means Southern Land - yet it is right up along the north coast. To an invading Viking however, this was their first landing on this southern land - it's all about perspective!

Caithness means the promontory of the cat people. It is believed that many of the early groups of people in the Highlands had particular animals they revered, and in this part it was the wildcat. (Scottish Wildcats still exist, but sadly only in very tiny numbers).

The front page of the Caithness Courier, reporting on the blizzard in 1978.

The Ord is 650 feet high and forms a real barrier. The top always gets large amounts of snow, and motorists face a challenge getting through in winter. In 1978, a huge blizzard left many cars completely stuck, and even caused a nearby train to derail. One couple died in their vehicle; another man died in his (though his dog survived). But miraculously, hosiery salesman Billy Sutherland survived more than 80 hours in his car (which was buried under more than 15 feet of snow). He wrapped himself up in tights and other products, and was none the worse for wear when a party of seven policemen found him.

As we continue north we go past more settlements - many now deserted - that were set up as herring fishing villages during the Clearances. Along this stretch they are all situated at the top of vertical sea cliffs. For example, in Badbea, both children and chickens had to be tethered to stop them falling off the cliffs. And at Whaligoe, where the men would bring in the catch on the boats to the harbour at the bottom of the cliffs, and the women were then expected to carry the fish, in creels on their backs, up a flight of 365 steps (one for each day of the year) carved into the cliff face, to get them to the homes where they would prepare the fish for sale.

A few of the 365 steps up the cliff from Whaligoe. They’re slippery even on sunny days… imagine trying them in wet weather…or in the dark! (photo by Undiscovered Scotland)

The (ruins of) the Castle of Old Wick, built by Harald Maddadson in the 12th century, served as a visual navigation aid to sailors in the North Sea. (photo: CastlesFortsBattles.co.uk)

We pass through a larger town here: Wick. The name is Norse simply for 'bay' and the settlement got a name-check in Viking Orkneyinga Saga when Earl Rognvald was entertained here by Harald in 1140. By mid 19th century Wick was the largest herring port in Europe, but the harbour could only be used at high tide. There is still a small fishing fleet based here, despite the major decline in the industry throughout the 20th century. One of the big industries here today is the manufacture of pipeline for the oil industry.

Further north we pass close to the twin castles of Sinclair and Girnigoe. They were built for the Earls of Caithness and protected by ditches spanned by a wooden bridge. They were separate but conjoined towerhouses, with Girnigoe built in late 15th century and Sinclair just over 100 years later. They were very definitely defensive in purpose, with gunloops on the seaward face and a wooden balcony from which missiles could be thrown. In the castle from 1570-76, the 4th Earl imprisoned his son, John, whom he suspected of plotting against him — possibly because during a conflict with the Murrays in Dornoch, after the Murrays’ capitulation John had not killed all the inhabitants of Dornoch as his father would have done. After 7 years, he died of thirst, starvation and, it is recorded, 'vermin'.

Castle Sinclair Girnigoe (photo: World Monuments Fund)

Castle Sinclair Girnigoe (photo: World Monuments Fund)

In the 17th century, George Sinclair the 6th Earl of Caithness transferred his title (including his estate, and the castle) to Sir John Campbell of Glenorchy as a repayment of a debt. However, when the Earl died four years later, this transfer was challenged by his cousin, George Sinclair of Keiss, who claimed the title should rightfully be his.

According to Keiss, the transfer of the title wasn’t a sober business deal at all — that instead Glenorchy, frustrated by the 6th Earl’s non-repayment on his debt, had arranged a deliberate shipwreck in which a cargo of whisky washed ashore near the Castle. He figured that the Earl — a man whose extravagant lifestyle had led him to become indebted to Glenorchy in the first place — would be likely to drink a lot of it at once. Then, once he was confident the 6th Earl was sufficiently drunk, Glenorchy had appeared on the scene and coerced him to transfer the title and the castle.

A 1648 painting of Castle Sinclair Girnigoe by an unknown artist

This dispute escalated into a complicated, violent multi-year conflict that engaged people all along the North Sea and beyond: even the Privy Council of Scotland got involved. A bloody battle took place at nearby Altimarlach along the River Wick, during which, it has been told, so many of Keiss’s supporters were killed near the riverbed that Glenorchy’s supporters could cross the river without getting their feet wet. But Keiss’s effort wasn’t over: he attacked Castle Sinclair Girnigoe in 1680, destroying it in the process and leaving it in the ruins it remains today. But guess what? He won. With the intervention of the Duke of York and later, King James II, by the end of September 1681 George Sinclair of Keiss was finally officially the 7th Earl of Caithness.

Finally we make it to John O'Groats: the most northerly settlement on mainland Britain, and the end point of the longest distance between 2 places on the island. If we had travelled as the crow flies from Land's End we would have gone 876 miles.

John O’Groats from the air. (Photo: Wikimedia user Madras9096)

The town was named after a man, Jan de Groot, from the Netherlands who bought a little piece of land here in 1490s. He was also granted the rights to run the ferry service from here to the most southerly point of the Orkney Islands (7 miles north - clearly visible as we look out to sea). The population of JoG is about 300 people, known as 'Groatsers'. Amazingly for such a small village, they have two football (soccer) teams!

There are also legends associated with the octagonal tower of John O'Groats' hotel building. The current tower is much more recent, however, it is said there was one of the same shape in de Groot's day. One story is that de Groot had 8 decendents, each of whom thought themselves the most important, so the tower was built with 8 walls and 8 doors, with an octagonal table inside, so each one of the sons could have their own door and they could all sit at the head of the table!

The octagonal tower at John O’Groats House

Another suggestion is that de Groot's family built an octagonal waiting room with 8 recesses, so that those waiting to catch the ferry would always be able to find an alcove that was protected from the wind, which up here can attack from any direction!

There is still a (summer only, passenger only) ferry service that runs to South Ronaldsay island, Orkney. It crosses over the Pentland Firth - the narrow stretch of water which is known as some of the most dangerous water around Britain. This is where the North Sea and Atlantic Oceans crash into each other - and with the water funnelled into that narrow stretch there are tidal races known as the Merry Men of Mey. The waves created by this, slightly further west along Scotland's north coast at Thurso, make it a very popular (if freezing) place for surfers!

Fancy a pint?

Unlike the Naylor brothers, who pledged to “abstain from all intoxicating drink” during their 1871 walk on this route, I’m not at all opposed to popping into interesting-looking pubs along the way. Here are a few along this stretch of the journey… this time, curated by Kirsten Griew, who has actually been there in person!

A perfect spot for a drink in our starting place of Dornoch is the Dornoch Distillery, situated in the old “Fire House” which was built in 1881, situated in the rear of the Castle’s garden. The castle also has a whisky bar — so depending on the weather, we can pick our site!

The micro-distillery is indeed small, but it somehow has enough room for the Thompson boys to create their own handcrafted ‘old style’ whisky and one shot ‘Thompson Brothers Organic Gin’.

In Wick, the Old Smiddy Inn is a lively local spot to grab a locally-brewed pint, and maybe enjoy some live music too. One online reviewer sold me on it, by writing: “Wonderful little country inn with fine beer and excellent scotch whisky. We were entertained by a local celebrity, Ray Bremner, who told stories and sang traditional songs in both Gaelic and English. The owners were behind the bar and made us feel very much welcome.” Sounds fun!

As you might guess from its name, the Old Smiddy occupies an old forge, where at one time a blacksmith worked. It seems poetic that it continues to be a community hub.

Finally, I can’t imagine a better place to enjoy a pint at the end of a long journey than the John O’Groats Brewery. Founded in 2015 as a four-barrel brewery, this brewery now produces a range of cask ales, distributed across the north of Scotland.

They expanded into the oldest building in John O’ Groats, “The Last House”, in 2019, installing a new brewery, bar and visitor centre.

Sustenance for the Hungry Vegan

Berriedale Beach, a short walk from the Braes Vegan B&B

In Berriedale, the Braes Vegan B&B offers vegan meals and comfortable accommodations to travelers passing through. In 2019, Barbara and Peter Gray opened the Braes, aiming to provide hospitality without harming animals and while helping guests optimize their health.

The Grays also manufacture and sell an array of vegan confectionery, including cookies and fudges. Mmm!

At the top of the famous staircase, the Whaligoe Steps Café and Restaurant offers numerous vegan options for every meal. One online reviewer mentions they aren’t all labeled as such, so asking your server is advisable.

The restaurant has won numerous culinary awards. Vegan dishes range from vegan miso ramen, dukka, crushed peas with mint and chili, hummus, muhammara, to soups and salads. House-made bread is available during your meal, and to go.

In John O’Groats, Stacks Coffeehouse and Bistro offers fresh, locally-sourced dishes, including lots of vegan options (and they’ll make adjustments to other dishes “on order,” to prepare them vegan too).

The Wymer family bought the derelict Caithness Pottery building in 2015 and with the help of local artisans and tradespeople, Stacks opened exactly a year later. Reclaimed materials and upcycled products were incorporated into the renovation to minimize waste.

Mom and daughter team Teresa and Rebecca run the place, and welcome everyone, regardless of diet.

Stacks Coffeehouse and Bistro in John O’Groats